Counting the Costs of “Independence Day”

If one of you wanted to build a tower, wouldn’t you first sit down and calculate the cost, to determine whether you have enough money to complete it? (Luke 14:26, CEB)

If we want to know the cost of building real freedom and in(ter)dependence in this country for everyone, then we have some accounting to do.

I began this series in the wake of the murders, and subsequent uprising of protests and actions on behalf of Ahmaud Arbery who was murdered by two white men while jogging, Breonna Taylor who was killed in her her own bed while sleeping by Louisville police (no arrests to date), and George Floyd whose death came after bring choked for 7 minutes and 46 seconds by a Minneapolis Police officer.

The goal of this series of blogs is to make space for my white friends to think with me about becoming anti-racist. We need to think about how the work is ours to do, and about steps we can take, both personally and corporately to undo white supremacy and white privilege(s). Those aspects of culture and psychology participate in deadly harm for Black people, Indigenous Peoples, most recent immigrants, and People of Color in the U.S.

+++++++

Today, July 4, the traditional day to mark America’s Independence from Great Britain, has come to be a celebration of both the Declaration of Independence and founding of the United States. You know the problems here. Not everyone was freed in that moment in 1776. And all the laws, ordinances and statutes passed since then still do not add up to freedom or equality for a majority of Americans.

You are invited to count the cost of white supremacy with me to the land, water, and people that share these United States. In the next few posts, I will share what I am learning about becoming anti-racist, and I’ll share ways you can join me by taking action.

You could start by watching and sharing this video featuring descendants of abolitionist, Frederick Douglass.

From Vague Ignorance to More Clarity

If you don’t know where you are standing, you don’t know who you are.

I grew up in Tennessee. And I lived in the Eastern part of the state from age 3 until I married and left home for graduate school. As a child and teen, I traveled to Nashville (in the middle of the state) often for school field trips and church outings and bowling tournaments (all stories for another day). I studied Tennessee history and toured the capital in the eighth grade. My interest in the stories and experiences of Indigenous peoples goes back to my first visit to Cherokee, North Carolina in the summer after sixth grade, and probably before.

Yet, my sense of history of the physical place where I currently reside on the west side of Nashville was vague at best and ignorantly wrong at worst. Some of what I learned recently surprised me. Some of it is more like a convergence of bits of knowledge that together are changing my sense of the whole picture. All of it is challenging my white privilege(s).

Like most white people in America, I didn’t have to know where I was or what that place meant, because everywhere I go, I can participate in the white ownership of space. I could not, however, always participate in the space that is owned by men. Much of my scholarship over the last 15 years worked on elaborating on that gendered problem.

With growing clarity I see how important it is to know where I am and what that place means. I need to know the geography, the history and the politics of the place(s) I live, work and worship. That work is part of undoing the socialization of white supremacy.

Overcoming Barriers

Today’s post is an attempt to show my work, as math teachers like to say. My move toward a better understanding of what it means to be anti-racist is ongoing and far from complete. However, I think we need to share how we are making these moves with intentionality and transparency. I, and we, need to be willing try and even mess up, in order to make any meaningful change.

One of the barriers to my own education about my whiteness, and its complicity in racism, has been a lack of solidarity and support from other white people committed to change. Thus, I am making space for two things in this series. First, I am amplifying voices of folks who live with the direct, detrimental and deadly effects of racism. Second, I am sharing stories of my own complicity in white supremacy culture and how I am working to become anti-racist.

White people need to cultivate a sense of understanding, empathy, imagination, and appreciation of the lives and contributions of Black people. Indigenous peoples, and People of Color to our shared life. White people are often unaware of the biases we carry, both implicit and explicit, because whiteness allows us to remain ignorant.

One of the important ways to change our implicit bias, according to psychologist and MacArthur “genius grant” winner, Jennifer Eberhardt, is to consistently and routinely expose ourselves to the voices and faces and lives of people against whom we are biased. Socialization into the culture of whiteness has prevented most of us seeing ourselves, our histories or our biases honestly.

You can test your implicit biases here.

Water

Our biases are not limited to the ways we see our neighbors. They also include the ways we inhabit the land and water where we live. We are 70% water: both the earth’s surface and human bodies. We need to understand the flow of water in our lives for many reasons including the care of the earth and our own understanding of where we live. More than ever we need to understand our impact on the planet and our own neighborhoods.

Part of white privilege is not knowing where we are or counting the cost of our impact on the land and water.

One important way to know the land you live on is to know your watershed address. Where does the water that rains down or rises up or flows across your dwelling place go?

My quest to learn my watershed address started over two years ago. It’s been slow going. When I attended the Alliance of Baptists’ annual gathering in Ohio, I heard Ched Meyers speak about the climate crisis. He and many other pastors and scholars, challenged us to consider global weather events and economic entanglements. They asked us to learn more about where we are.

The conference planners urged use to look up our watershed address. That very week, the EPA took down huge parts of its site, including the pages on watershed and the mechanism for looking up one’s address. The current presidential administration defunded the EPA, including decommissioning that portion of the site.

Know Your Watershed

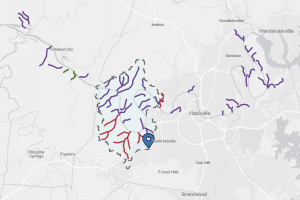

I spent a lot of time searching through other sites and eventually determined something close. A google map showed me that the waters from my backyard drain* to the Ewin Branch. From there they flow to Davidson Branch and into the Cumberland River.

A more comprehensive local website helps me to name my connection to the slightly larger Middle Cumberland Watershed. The two creeks in my immediate neighborhood need better care.

Last week I found the watershed address look-up is working again. The U.S. Geological Survey now hosts the search tool. In the U.S. you can look up your watershed address and know more about the water in your world. If you are in Middle Tennessee, however, I recommend searching the Cumberland River Compact.

Counting the cost of where our water goes and how we cared for it matter. These costs and cares are deeply related to the ways White people and have it the culture of white supremacy and benefit from white privilege(s). The impact of our lack of care for land and water it’s not just harmful but deadly.

If you look after children at your place, you might like this JULY challenge. It will help you know your watershed in a better way.

++++++++

Next in the series, I will share what I’m learning about the land I live on. I will tell you what I know about who stole this land, who traded it, and how enslaved people tended it. Many events and people shaped this place where I live. Please join me in the work of coming to consciousness, counting the costs, and dismantling systems of racism.

- Image: bumble bee on a butterfly bush in my back yard with drainage line visible in the background.